The bryophyte groups

What is a moss?

A moss is a flowerless, spore-producing plant - with the spores produced in small capsules. The introductory WHAT IS A BRYOPHYTE? page noted that bryophytes have a gametophyte stage and a sporophyte stage. The spore capsule, often with a supporting stalk (called a seta), is the sporophyte and this grows from the gametophyte stage.

You will commonly see the statement that a moss gametophyte consists of leaves on stems. That statement is so close to the whole truth that it's no surprise it's so commonly used.

When a moss spore germinates it first develops a protonema. This is a filamentous to sheet-like growth form, often with a strong resemblance to an algal colony or a fern prothallus. In due course one or more stems grow from the protonema and leaves develop on the stems, giving rise to one or more leafy-stemmed plants. In almost all moss species, the protonemata are ephemeral, with the leafy-stemmed plants the persistent and dominant growth form. But there are exceptions. In some species the protonema is persistent and the leafy part is ephemeral. The term gametophore is used for the stems-and-leaves part and the protonema and gametophore together make up the gametophyte. Now, as already noted, in almost all species the protonema is ephemeral and insignificant when compared with the leafy-stemmed growth. So the leafy-stemmed part is the gametophyte in the great majority of species. It now becomes clear why that fact is often generalized to the statement that the gametophyte in all mosses is leafy-stemmed. For more about the early development, see the LIFE CYCLE SECTION. In contrast to the case in mosses, a liverwort protonema is rudimentary.

The aim of this page is simply to describe the features you can see in a moss - in both the gametophyte and sporophyte stages. You will see some, but by no means all, of the variety in moss gametophytes and sporophytes. This page gives an overview of the features found in mosses and there are links to more details on some of the topics.

While the identification of mosses often requires the use of a microscope, you can learn a lot just by using your eyes and a handlens that magnifies 10 times. In the reference button you’ll find some books with colour photographs of Australian mosses. Looking through them will give you a good introduction to moss diversity![]() .

.

The following references are very useful for more detail about this great diversity, from the macroscopic view to the microscopic level. Much of the following information on this page has come from these books![]() .

.

Before going on it’s worth noting that you might confuse mosses with leafy liverworts (which also have a leaves-on-stems gametophyte stage). However, once you’ve read this page as well as the WHAT IS A LIVERWORT? page, you will have all the information to let you tell the two apart. For convenience, the distinguishing features of all the bryophytes are summarised on the page that lets you answer the question: WHICH BRYOPHYTE IS IT?

Moss gametophytes

While it may be true to say that a moss gametophyte has "stems and leaves", that statement leaves a lot unsaid. There is a lot of complexity and variety in these ”stems and leaves" plants.

Stems

Moss stems are generally fairly weak and, if free-standing, fairly short. Stem colour varies from green ![]() to shades of brown, for example, Ptychomnium aciculare. Stems are often green when young, with chlorophyll in the cells.

to shades of brown, for example, Ptychomnium aciculare. Stems are often green when young, with chlorophyll in the cells.

The mosses in the families Dawsoniaceae and Polytrichaceae provide striking exceptions to the general rule stated at the beginning of the previous paragraph. Within these families the stems are fairly firm, with the plants being upright and quite robust. In this photo of a Dawsonia ![]() you can see the brown stems quite clearly. Polytrichum or Dawsonia plants can be quite tall, with the free-standing stems of some species growing to over 60 centimetres in height. Hence it is not surprising that people often mistake these mosses for herbaceous flowering plants. Though the stems in the Dawsoniaceae and Polytrichaceae are fairly firm, they contain no lignin and are not woody.

you can see the brown stems quite clearly. Polytrichum or Dawsonia plants can be quite tall, with the free-standing stems of some species growing to over 60 centimetres in height. Hence it is not surprising that people often mistake these mosses for herbaceous flowering plants. Though the stems in the Dawsoniaceae and Polytrichaceae are fairly firm, they contain no lignin and are not woody.

Two growth forms - tufty and trailing

There are essentially two growth forms for moss plants. In one the stems are basically erect, with just one upright stem per plant or with the initial erect stem producing some branches, depending on the species ![]() , giving the individual plant a tufty or shrubby appearance. In the other growth form the moss will have mostly trailing stems. If the stems cling to the substrate the overall appearance, to the naked eye, will be of a creeping plant

, giving the individual plant a tufty or shrubby appearance. In the other growth form the moss will have mostly trailing stems. If the stems cling to the substrate the overall appearance, to the naked eye, will be of a creeping plant ![]() but in some species they hang, almost curtain-like, from branches

but in some species they hang, almost curtain-like, from branches ![]() . The trailing mosses are typically highly branched with the branches growing along the substrate - but many such species also produce short, upright branches. Branches develop from surface cells in the originating stem and in most mosses branches are simple, single outgrowths from the originating stems. In Sphagnum you will see branches developing in fascicles. Within such a fascicle, some of the branches will be stout and spreading, while others are slender and drooping.

. The trailing mosses are typically highly branched with the branches growing along the substrate - but many such species also produce short, upright branches. Branches develop from surface cells in the originating stem and in most mosses branches are simple, single outgrowths from the originating stems. In Sphagnum you will see branches developing in fascicles. Within such a fascicle, some of the branches will be stout and spreading, while others are slender and drooping.

In species with an upright growth form the stems may be very short (almost non-existent) to quite long - as already noted for some Dawsonia species. If there is only a very rudimentary stem the plant will look like a bunch of leaves growing from just a single point. In genera like Polytrichum and Dawsonia the individual plants are typically just single stems, with branching rare. Amongst the upright mosses there are the so-called "dendroid" mosses, which have a spread of branches atop a vertical stem ![]() . The word "dendroid" means "tree-like" and it's easy to see how apt that term is. In some cases, instead of branches in all directions, there'll be a fan-like spread of branches. You'll also see such mosses called "umbrella mosses" - an equally apt descriptive expression.

. The word "dendroid" means "tree-like" and it's easy to see how apt that term is. In some cases, instead of branches in all directions, there'll be a fan-like spread of branches. You'll also see such mosses called "umbrella mosses" - an equally apt descriptive expression.

There are many erect-stemmed species of moss where the plants grow very closely together in mat-like or cushion-like colonies. In such cases it can be hard (or even impossible) to make out the individual plants, unless you carefully tease apart a small section of the mat or cushion to see what it’s composed of. Here’s a photo of a large colony of a silvery-green moss, Bryum argenteum ![]() and here’s a closer view of the upper surface of such a moss colony when wet

and here’s a closer view of the upper surface of such a moss colony when wet ![]() . You can see a somewhat cobblestone-like surface. If you take a very small sample from the colony and look at it side-on you see this

. You can see a somewhat cobblestone-like surface. If you take a very small sample from the colony and look at it side-on you see this ![]() . What you see in the final photo is a small number of individual plants, packed together very tightly.

. What you see in the final photo is a small number of individual plants, packed together very tightly.

In the case of the cushion-like growth, much of the cushion may be composed of dead material (photo right). As the stems grow, the older leaves (lower down on the stem) die, leaving a living green layer atop a mass of brown, dead material. That brown section will be a mix of rhizoids, dead leaves and stems, and other organic matter that may have been trapped by the plants making up the moss-cushion. You can still make out some leaves in that mass of brown. As the stems continue to grow, more and more dead material will accumulate. Such largely-dead cushions are more characteristic of moist areas, where they can grow to a considerable size. It is common to see sizable green cushions, on rock or trees for example, in moist habitats.

Instead of growing in cushions, you can also get simple-stemmed species where the plants grow separately from each other. Then they look like many small, green fingers poking up from the soil.

In a creeping moss there may be short, leafy branches that grow away from the substrate but such branches are simply off-shoots from the creeping stems. There are also moss species that produce long, trailing stems but where (apart from a small attachment area) the stems don’t cling to anything. In such cases you can see a pendulous, curtain-like growth, such as that of Papillaria flavolimbata ![]() .

.

In some species of clinging, trailing-stemmed mosses the short branches that grow away from the substrate may be very easy to see whereas the clinging stems may be hard to see. For example, the upright branches may be so numerous as to hide the trailing stems or perhaps it’s a species with very few leaves on the clinging stems, so making it harder to realize there is stem there. Or it may be that the main stems are growing in bark cracks or are hidden by leaf litter. In all such cases, unless you look carefully, you could easily mistake the separate upright branches of the one, creeping moss plant as numerous individual plants of a tufted species.

In Gigaspermum repens ![]() there is a creeping, largely leafless, underground stem that is rarely seen. All that is visible above ground are short, erect leafy branches (1 to 3 millimetres tall). It would be easy to think of each such leafy branch as a separate plant.

there is a creeping, largely leafless, underground stem that is rarely seen. All that is visible above ground are short, erect leafy branches (1 to 3 millimetres tall). It would be easy to think of each such leafy branch as a separate plant.

Rhizoids

All mosses have rhizoids. These are anchoring structures, superficially root-like, but without the absorptive functions of true roots. Moss rhizoids are always multi-celled and often branched, whereas liverwort rhizoids are mostly single-celled and rarely branched. Rhizoids are present at the protonemal stage. Once stems have developed rhizoids occur at the bases of stems (in the tufty species) or along the stems (in the trailing mosses). While all mosses have rhizoids, some species may be dense with rhizoids while on others the rhizoids are sparse ![]() .

.

Moss rhizoid systems can be extensive. There are examples of soil mosses where the above-ground plant may be only a centimetre or so in height - but where the rhizoid system reaches three or more centimetres into the soil. Rhizoids aren't roots and don't conduct water and nutrients internally, but a mass of rhizoids can conduct water externally by capillary action. In some species the rhizoids are wound together, almost rope-like, and such strands are very effective at moving water by capillary action.

Leaves

In a dry moss plant the leaves are typically folded into or curled around the stems. In such cases the leaves unfold or uncurl when the plant becomes wet. Thus a moss can look quite different in the wet and dry states. However, there are species where, even in a moist plant, the leaves still clasp the stem.

The individual leaves are small, generally from half a millimetre to three millimetres long. They are always attached directly to the stem, never with a short stalk. In most genera the leaves are just one cell thick, making them translucent. In many such genera the leaves are thickened along their long central axes. Such a thickening is called a nerve or costa. There are a few genera (such as Leucobryum and Sphagnum) where the leaves are several cells thick. Moss leaves generally taper to the tip (though the tapering may be sudden or gradual). The tip may continue as a long hair-like extension, called a hairpoint.

The photo (right) shows a colony of Campylopus introflexus, a common and widespread species in Australia. In this species each leaf has a hairpoint and the photo shows the hairpoints quite clearly. Leaf bases may vary, depending on species, being anything from much narrower to much wider than they are at mid-leaf, and they may be long or short in relation to width. The leaves typically have smooth or almost smooth margins. The margins may be toothed but you don't get the heavily divided leaves that are common in the leafy liverworts.

Different parts of the plant may have different types of leaves. For example, in many trailing species the leaves on the upright branches are different to those on the creeping stems. In many mosses, whether trailing or tufty, the leaves that surround the egg and sperm producing organs differ from the other leaves on the plant.

There's more about bryophyte leaves in the LEAF SECTION.

Antheridia and archegonia

The male and female gametes (eggs and sperm) are produced on the gametophyte (in special structures called antheridia and archegonia, respectively) and a fertilized egg will develop into a sporophyte. Thus the spores are part of the sexual reproduction cycle. There's more about this in the REPRODUCTION SECTION. Mosses can be divided into two broad groups, depending on where the archegonia are produced. In the acrocarpous mosses the archegonia are produced at the ends of the main stems. In the pleurocarpous mosses the archegonia are produced on short side-shoots, not on the main stems.

Moss sporophytes

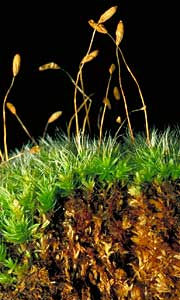

A moss sporophyte consists of a spore-containing capsule, possibly sitting atop a stalk (called a seta). In this photograph ![]() you can see many brownish sporophytes (the stalked spore capsules) that have grown from the greenish, leafy-stemmed gametophyte. The sporophyte's development is discussed in the SPOROPHYTE DEVELOPMENT SECTION.

you can see many brownish sporophytes (the stalked spore capsules) that have grown from the greenish, leafy-stemmed gametophyte. The sporophyte's development is discussed in the SPOROPHYTE DEVELOPMENT SECTION.

In almost all moss species the capsule has a well-defined mouth at the end opposite the stalk or the point attaching the capsule to a stem. When there is a mouth, the spores are released through that mouth. There is a very small number of mouth-less mosses - such as species of the genus Andreaea. This genus is commonly found in polar areas and in sub-alpine to alpine areas (and even alpine areas in the tropics). The capsules of Andreaea do not have mouths. Instead they open by slits in the sides of the capsules. In some genera (such as Archidium) the capsules have neither mouths nor splits in their slits in their sides. Instead, the capsules rupture irregularly.

The mature spore capsule may (depending on species) hang down, stick up - or be held at any angle in between. The way the capsule opens (mouth, side slits, irregular rupturing) and the orientation of the capsule play important roles in the way in which spores are released and there's more about spore dispersal in the in DISPERSAL SECTION.

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)